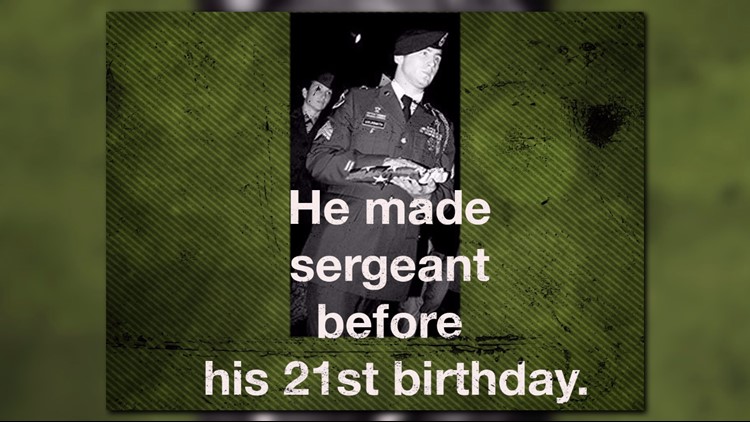

TUCSON - Looking at the first half of his service record, Jeff Osterhoudt could be Captain America.

He was an Army Ranger with combat tours of duty in Iraq and Afghanistan. He was selected for special operations, assigned to the elite 1st Special Operations Detachment - Delta, also known as Delta Force.

But Osterhoudt's time in the military could not last.

His personal life was in tatters, his first wife had committed suicide and he had been deployed to two war zones. Those things haunted him, as well as the things he had done.

HAVE YOU SIGNED? Sign the Fairness for Veterans petition to Congress

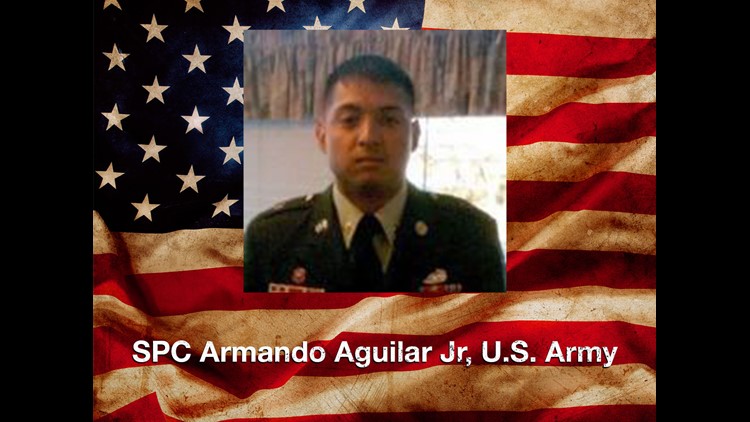

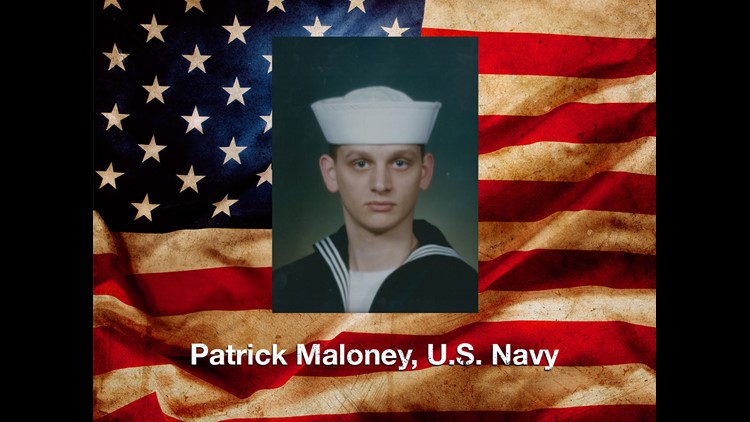

Faces of Charlie Foxtrot

In Iraq, Osterhoudt and his squad were chasing a target who had already been wounded. While they were searching for him, a man and his son came out to the street, the father holding an AK-47.

"Well, then dad raises his AK up and I ended up killing his dad," Osterhoudt said, looking at the ground. "Then the kid starts reaching down and I remember telling myself, 'Don't do it, don't do it.' And the kid grabs the gun. I'm like, 'Don't point it' ... and the kid starts to raise it up and I shot him and killed him."

That moment haunts him years later.

RELATED: Resource guide for veterans

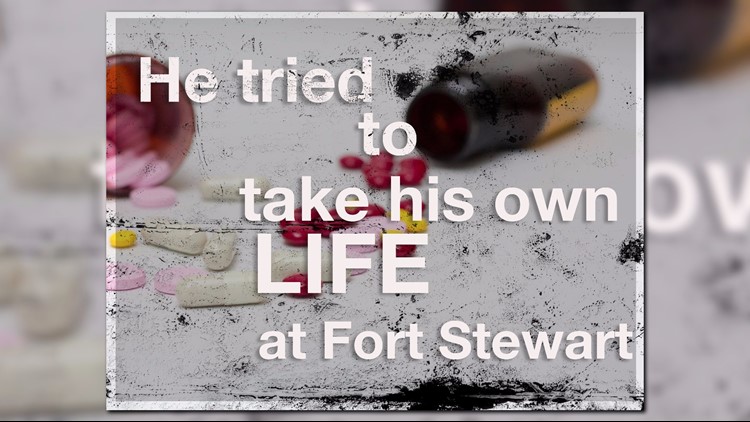

It all combined in a perfect disaster on a military base in Colorado.

Osterhoudt was addicted to methamphetamine. One day he had convinced himself that he would be drug tested and had bought a detox kit. He was acting strangely when military policemen pulled him over. First, the MP found Osterhoudt's handgun, a gun that was not registered and not allowed on the base. Then, the MP found a receipt for the detox kit.

Osterhoudt was arrested and confessed.

"My life was over," Osterhoudt said. "That was a very dark time in my life."

Initially, he was given a less than honorable discharge. But Osterhoudt showed progress and military officials upgraded his discharge to simply, "General (Under Honorable Conditions)."

It's not the same as an honorable discharge, and people noticed.

He sought help from the VA hospital system, but couldn't connect with the therapist. He was a special forces soldier who'd gone through things that most people couldn't imagine. She had never been on the front lines.

Osterhoudt left and found his own therapist, who he couldn't afford.

"In all honesty, she lost money treating me," Osterhoudt said. "But because of her compassion for soldiers and because of her desire to help us, she kept seeing me for 22 months straight."

Now Osterhoudt is fighting to get that discharge upgraded to "Honorable."

He doesn't believe that his discharge was wrong, or that he shouldn't have been punished. But Osterhoudt said his drug use was a symptom of something that no one caught: his PTSD.

Osterhoudt was diagnosed with PTSD, but he believes he showed signs and symptoms long before then.

"It's a very common theme," attorney Kristine Huskey said.

Huskey runs the Veteran's Advocacy Law Clinic at the University of Arizona. She and her staff try to help veterans with "bad paper" discharges upgrade their statuses.

"It's drugs, alcohol, AWOL's (Absent Without Leave), talking back, aggressiveness," Huskey said. "Those are all symptoms of PTSD and TBI (Traumatic Brain Injury)."

In 2014, former Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel wrote a memo explaining the review boards should err on the side of veterans if they had been diagnosed with PTSD.

So far, Huskey said, the clinic hasn't had a single bad paper discharge overturned.

"They spend a page and a half," Huskey said. "They don't even address our arguments."

Huskey and the clinic are now working on Osterhoudt's case.

Meanwhile, Osterhoudt volunteers to help returning veterans adjust to life away from the war.

"That changes anybody, I don't care who you are," Osterhoudt said. "And there's a lot of societies around the world that expect that change when their guys come back. Our doesn't."

"But the expectation needs to be there that when you go overseas, you're not coming back who you were before," Osterhoudt said.