Jamil Al-Amin’s life has always been a fight. First, for civil rights and justice during the Civil Rights movement. Now, he's fighting for his own freedom.

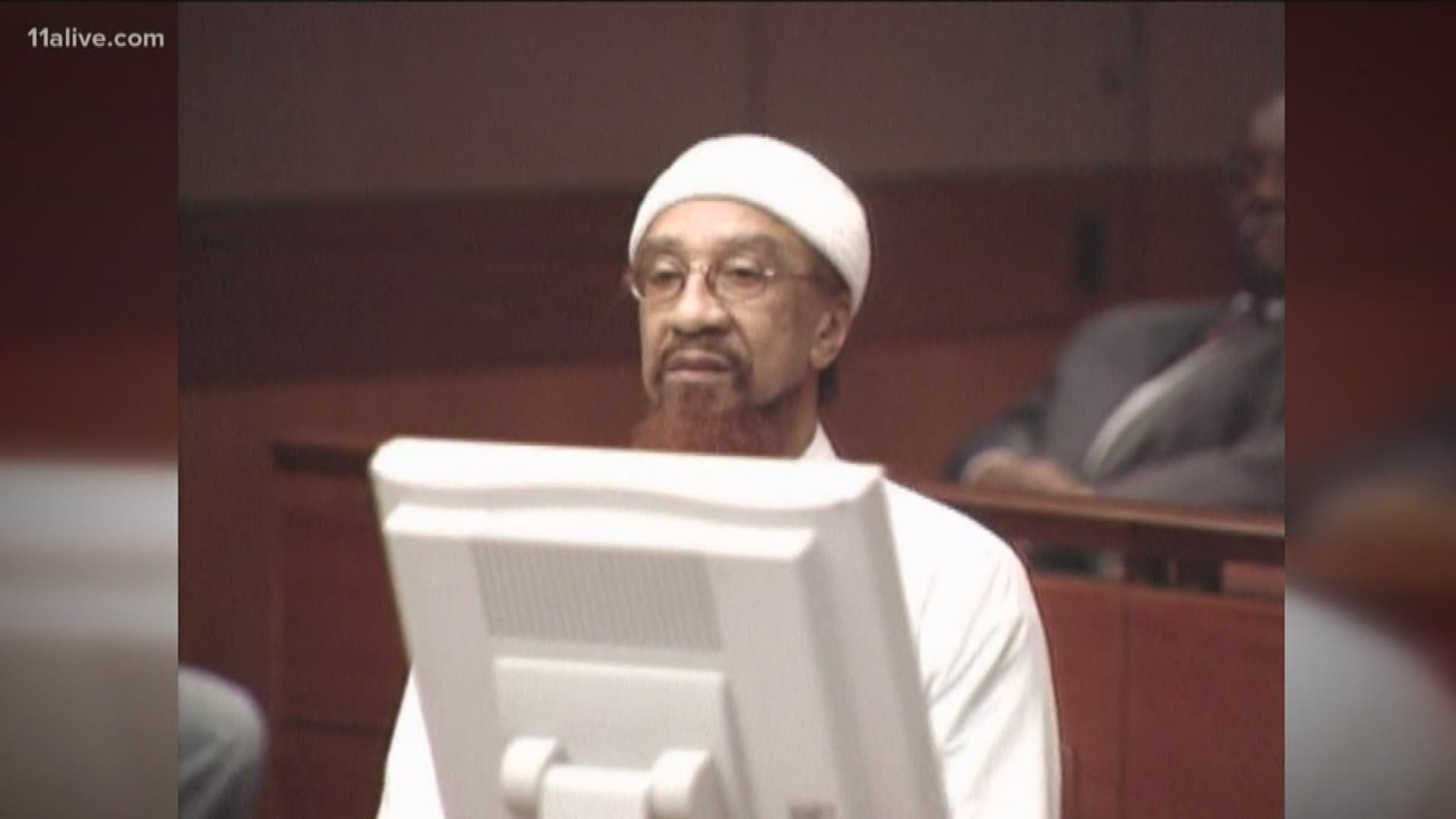

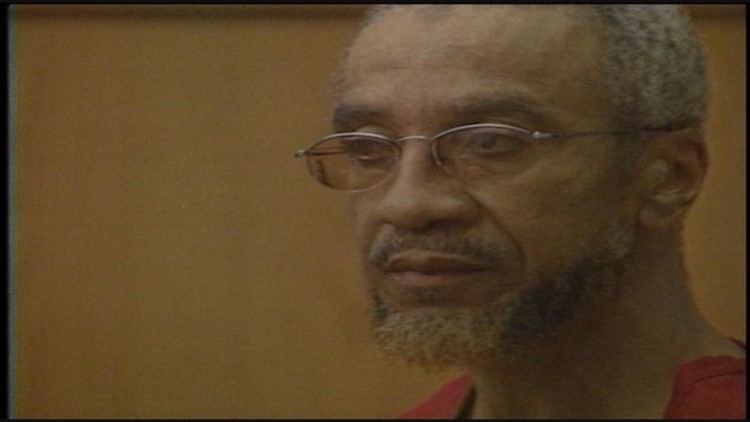

The respected Muslim cleric and former Black Panthers leader, A.K.A. H. Rap Brown, is a convicted cop killer who has spent the last 17 years behind bars for the murder of Fulton County sheriff’s deputy Ricky Kinchen. On May 3, the 75-year-old man's legal team will go to court in an effort to get his conviction overturned. His supporters said that the jury overlooked evidence that raises questions about the murder – and who did it.

“Just look at what happened. Maybe you’ll come to the conclusion … that someone may have had it in for my father,” his son, Kairi Al-Amin, told 11Alive's Doug Richards.

Al-Amin was just a schoolboy when a Fulton County jury sentenced his father to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

“I just want you to come to the conclusion that maybe there was another option. Maybe he didn’t do this. Maybe we should look at this again at trial,” he said.

THE SHOOTING THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

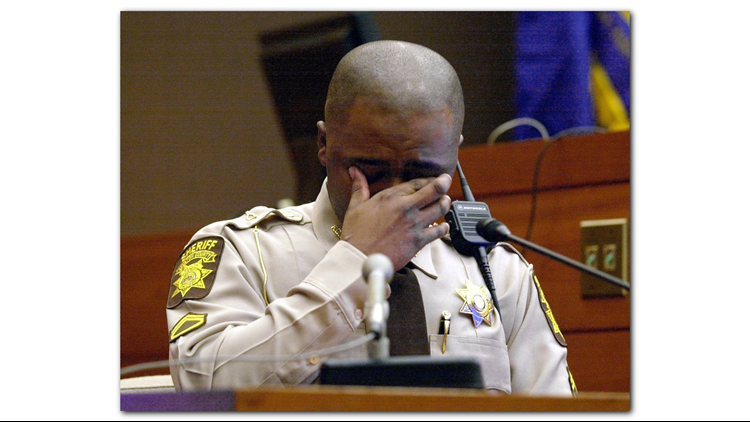

On March 16, 2000, Kinchen and his partner, Deputy Aldranon English, went to Al-Amin’s home to serve a warrant for failing to appear in court on charges of driving a stolen car and impersonating a police officer. Kinchen and English determined the home was unoccupied and drove away. Shortly after, they were passed by a Mercedes heading toward the home. Kinchen turned the patrol car around and the officers attempted a traffic stop near Al-Amin's grocery store when the occupant opened fire, killing Kinchen and wounding English.

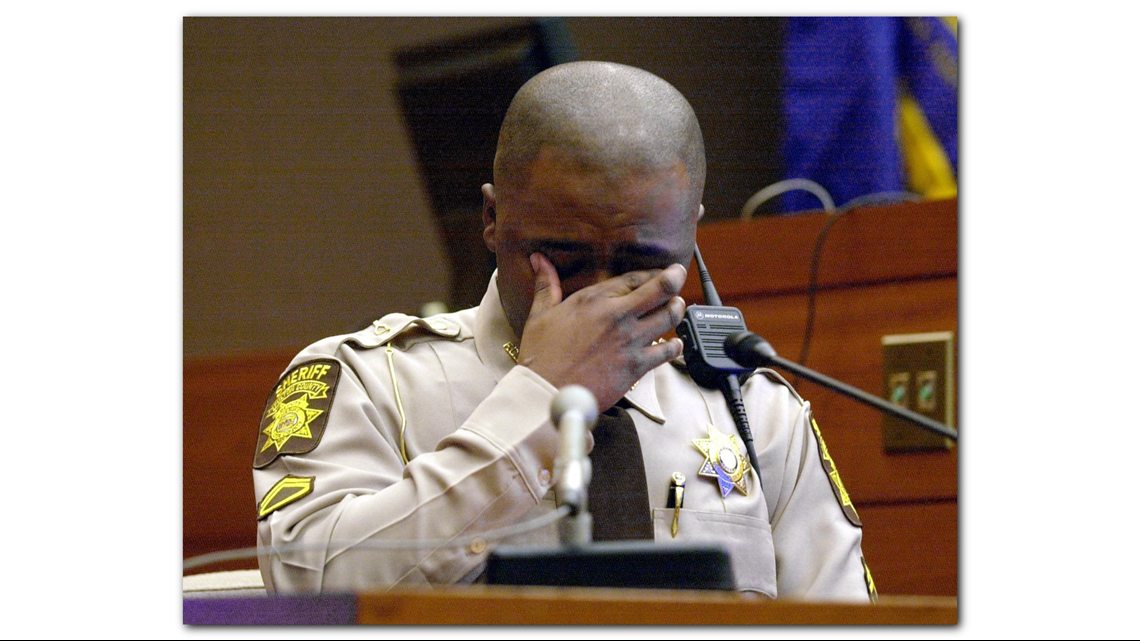

Kinchen left behind two young girls and a wife, Sherese Kinchen.

"Ricky was not only my husband. He was my friend for 18 years. He was my confidant and my rock and now he's gone. Some days, I just sit and cry. Some days, I think Ricky will walk through that door at any moment, but I know he won't," Sharese Kinchen said in court.

"So, I wipe my tears and stay strong for my children, because I know that they hurt too."

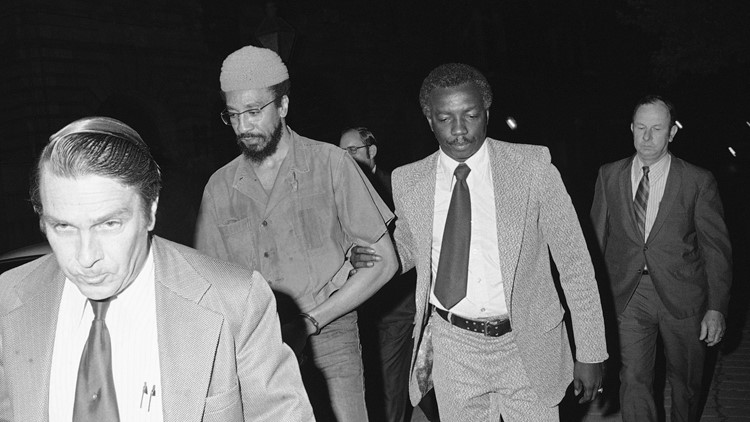

After a four-day manhunt, police tracked Al-Amin to White Hall, Alabama. They found a Mercedes nearby, pocked with bullet holes. Police testified Al-Amin fired on them when they attempted to capture him and testified that weapons found during the arrest match the ballistics of the bullets fired at deputies Kinchen and English.

Jurors in Al-Amin’s murder trial saw the guns seized from the Muslim cleric and heard eyewitness testimony from English -- who identified Al-Amin as the gunman.

“The truth of the matter is, the defendant was standing outside the black Mercedes, (who) shot me with the assault rifle was the only one I saw that night,” English said.

Al-Amin’s lawyers argued that he was innocent. They noted that his fingerprints were not found on the murder weapon and he was not was not wounded in the shooting – contradicting police testimony that they shot the suspect. Al-Amin also didn’t fit the profile of the man English described after the attack; he swore the shooter was short and had gray eyes. But Al-Amin is over 6 feet tall with brown eyes. When he was apprehended in Alabama, he also had no signs of any shooting-related injuries.

"Do I believe there was a conspiracy? Absolutely ... did people conspire to make something happen? Yes," Kairi Al-Amin said. "We know he was a target in the 60s. They read transcripts of my phone calls in court, so they are monitoring him ... it was to see what we were talking about. Luckily, we talk about basketball."

On March 22, 2002, Al-Amin was convicted of murdering Kinchen along with a dozen other charges. He was sentenced to prison without the possibility of parole. On the same day Al-Amin’s conviction was delivered, the state court trial ruled that the original traffic stop that started the whole ordeal had violated Al-Amin’s Fourth Amendment rights of protection from unreasonable search and seizure – making it illegal.

H. RAP BROWN BECOMES JAMIL AL-AMIN

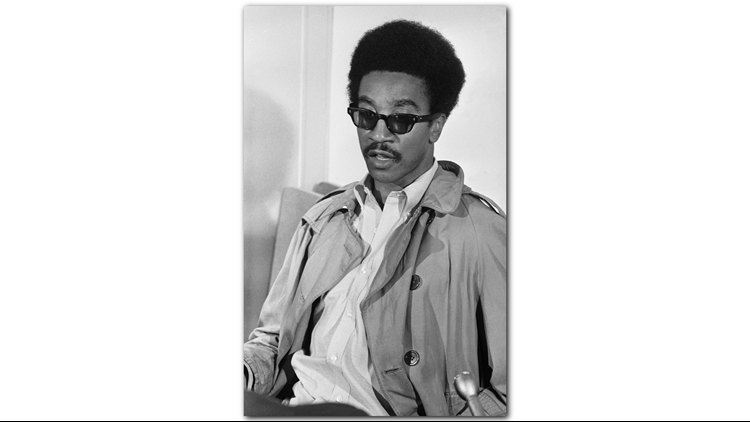

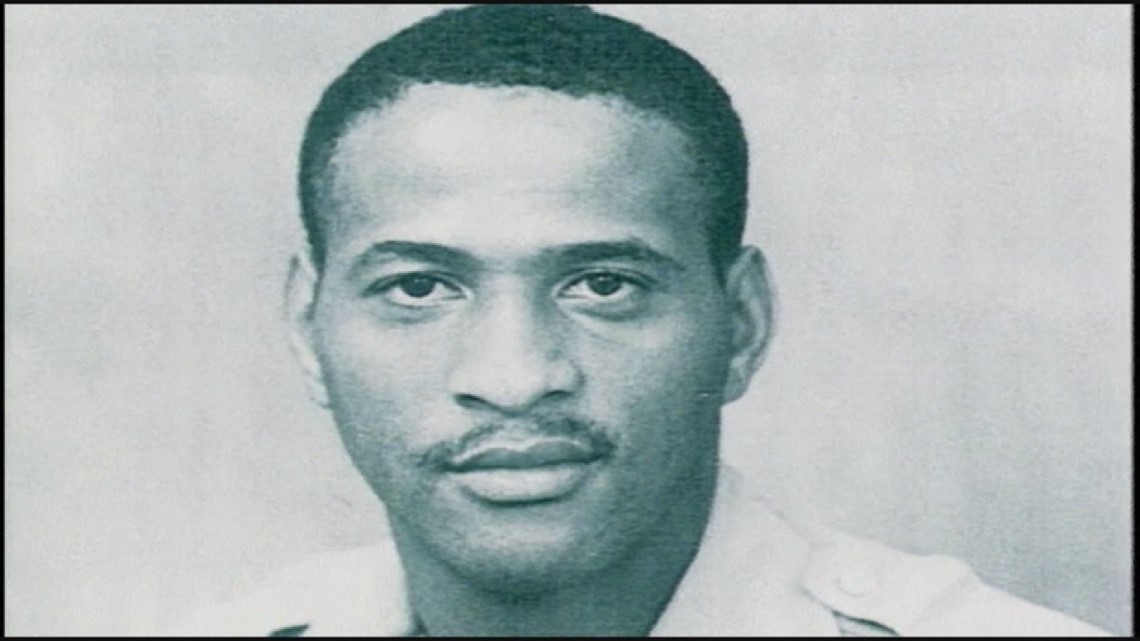

Al-Amin’s story is steeped in race relations and upheaval. If Martin Luther King Jr. represented the heartbeat of the nonviolent civil rights movement, Al-Amin may have represented its feverish impatience – and seething anger.

“How many white folks you killed today?” Al-Amin is heard asking a crowd in Oakland, California, in 1968.

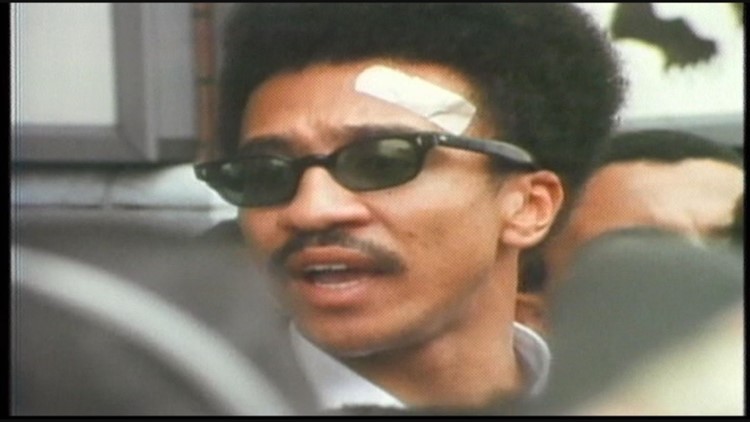

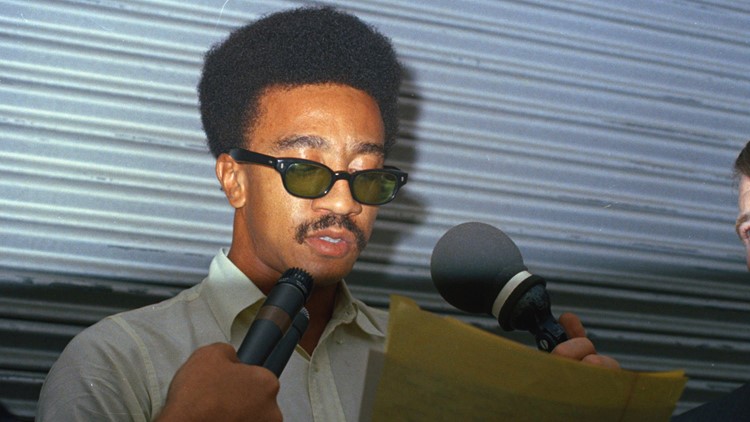

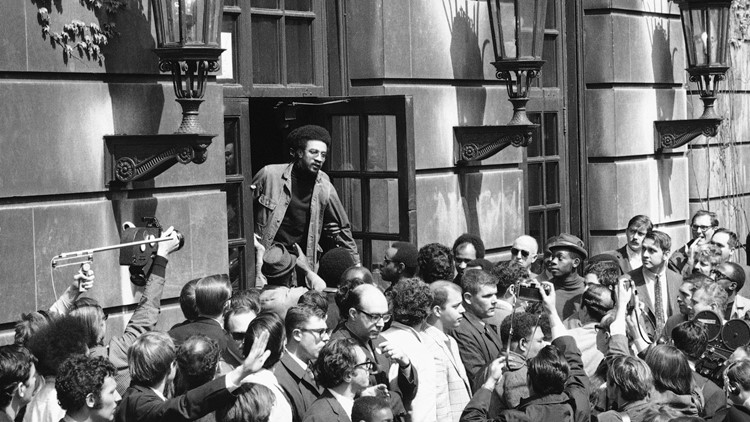

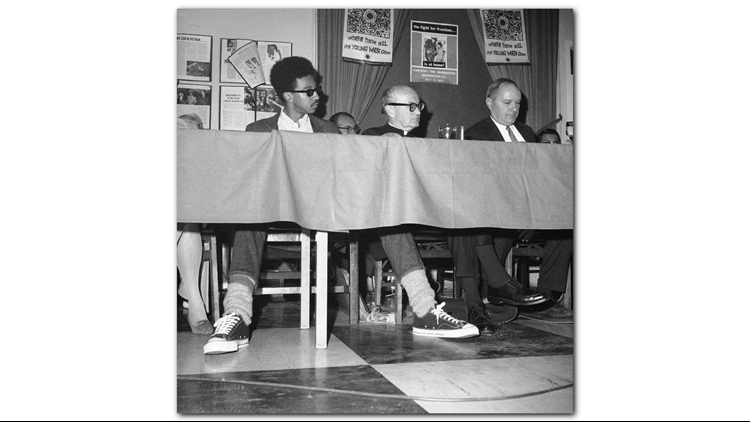

Al-Amin became a figure in the civil rights movement as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee but tore away from nonviolence to embrace the militant Black Panthers – famously declaring that “violence is as American as cherry pie.”

In the late 1960s, Al-Amin was convicted on federal charges of inciting a riot and carrying a gun across state lines.

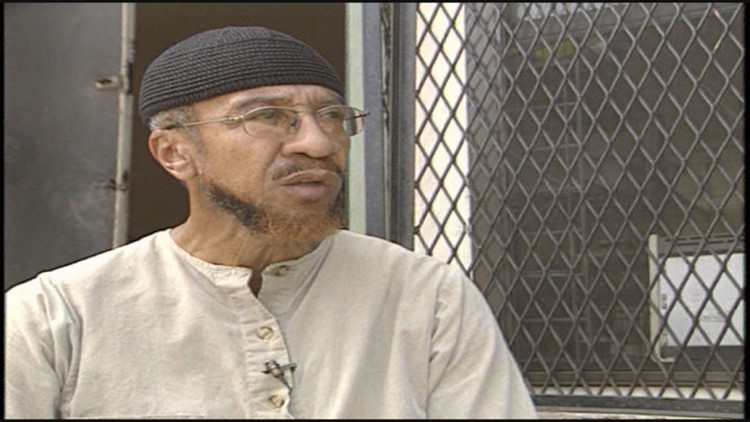

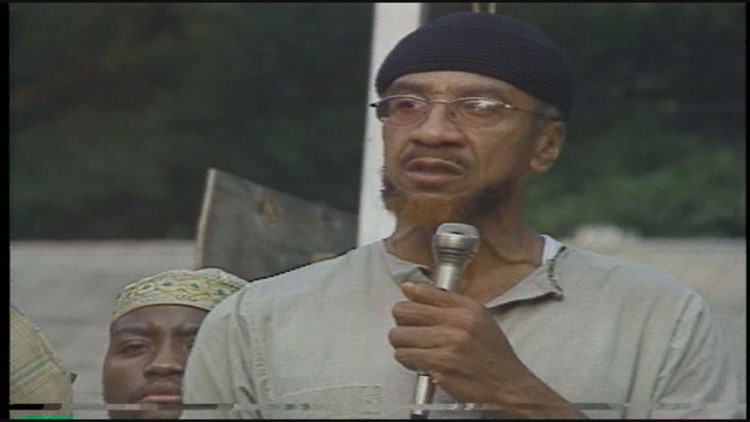

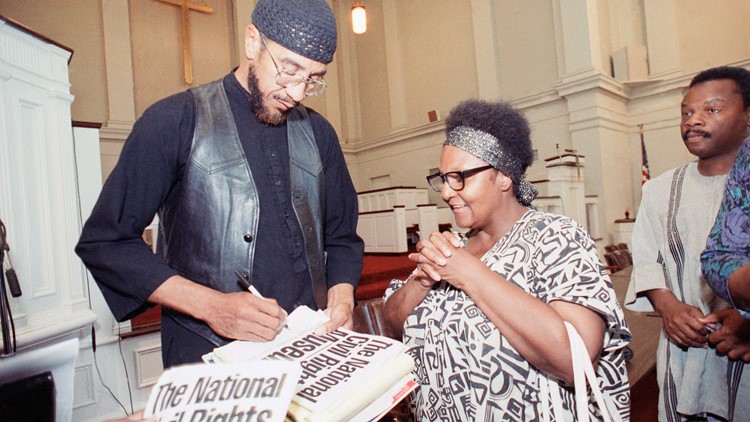

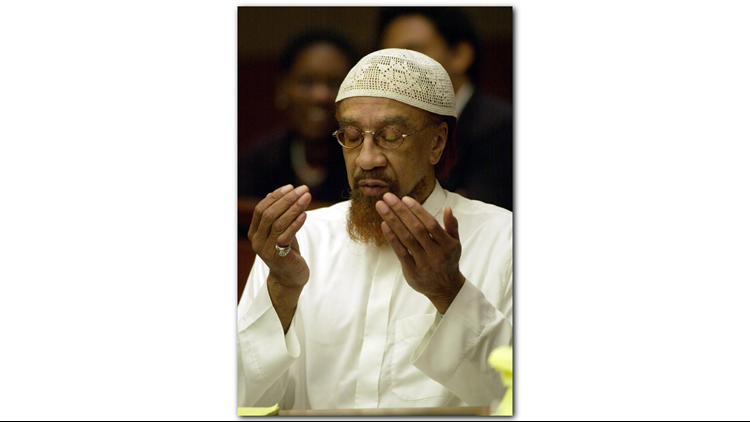

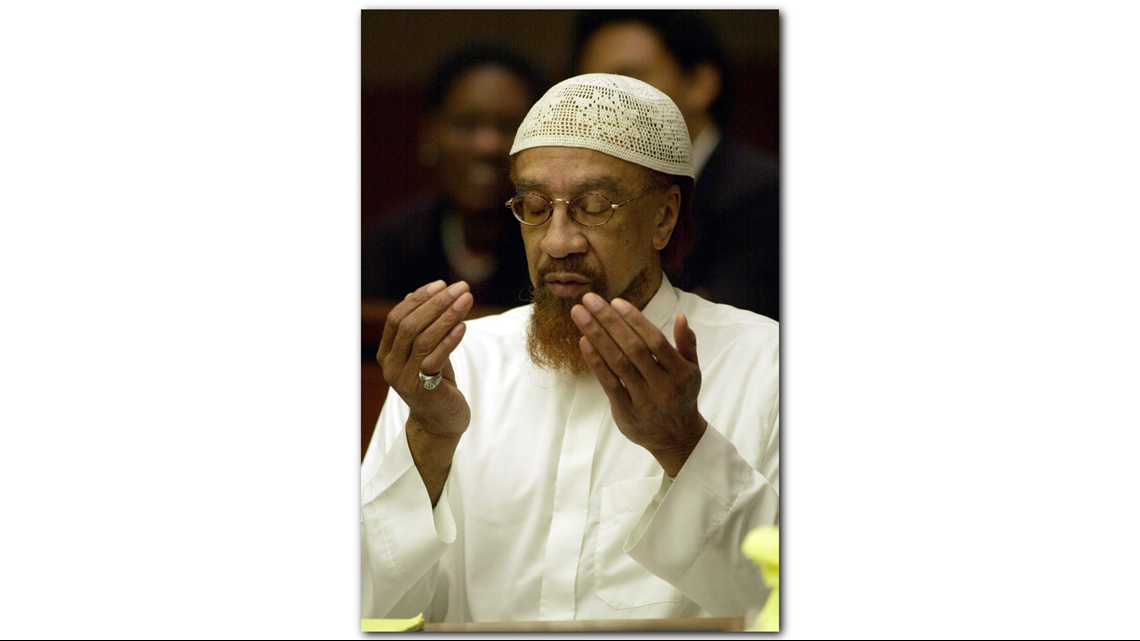

While in prison, Al-Amin became a Muslim and changed his name to Jamil Al-Amin. When he was released from prison, he moved to Atlanta’s West End and quietly became a religious leader in the community. He would eventually lead one of the nation’s largest black Muslim groups -- the National Ummah. It formed at least 36 mosques around the nation and is credited with revitalizing poverty-stricken areas.

While Al-Amin lived his life as a changed man and a Muslim cleric, he said law enforcement didn’t treat him that way, claiming he was a constant target of police harassment.

“They’ve continued their persecution of me and by targeting me for the last seven years that I know of, to harass us,” Al-Amin told 11Alive in 1995.

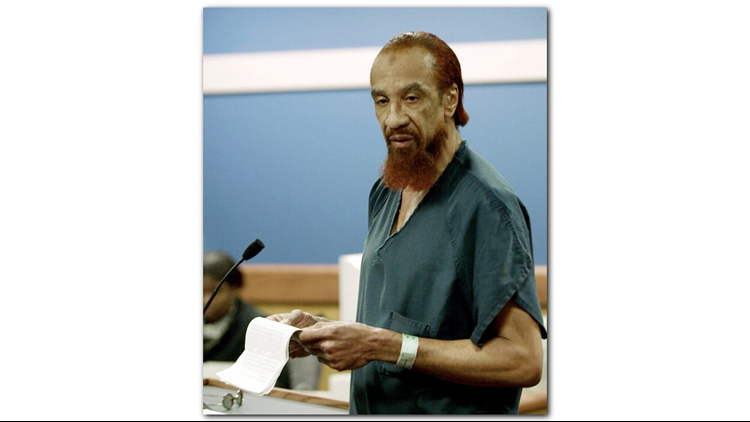

BACK IN THE COURTROOM

In 2004, Al-Amin got another chance at freedom, after another man confessed to the crime. Otis Jackson, a man incarcerated on unrelated charges, confessed to the shooting two years before Al-Amin’s conviction. However, the court did not consider Jackson’s statement as evidence – even though his statements corroborated details from 911 calls made from the scene, including a witness who described seeing a bleeding man limping away and trying to get a ride.

At trial, prosecutors pointed out that Al-Amin never provided an alibi for the night of the shooting and didn’t explain why he fled to Alabama. During trial, Al-Amin did not explain why the weapons used in the shootout were found near him during his arrest.

In May 2004, Al-Amin's conviction was upheld in a unanimous vote in the Supreme Court of Georgia.

In 2007, Al-Amin was transferred to the ADX Florence supermax prison in Florence Colorado. In 2014, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma and was transferred to a federal medical center in North Carolina.

Currently, he is incarcerated at the U.S. State Penitentiary in Tuscon, Arizona.

ANOTHER CHANCE AT FREEDOM

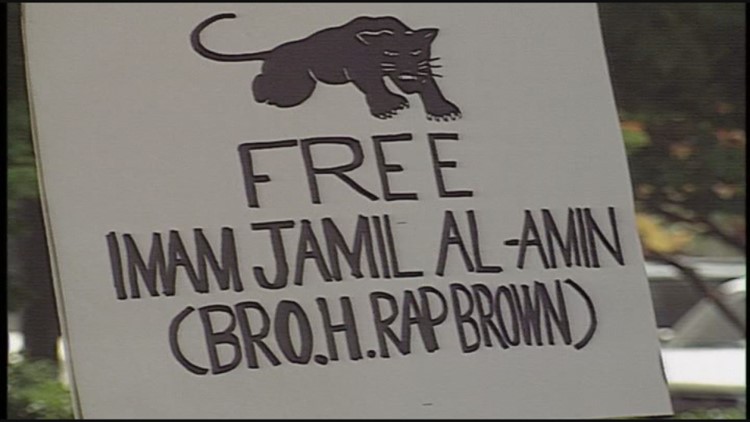

Just as many Atlanta Muslims and Black Panthers rallied around Al-Amin 17 years ago, attorneys are ginning up support as they seek a new trial for the cleric, ahead of his court hearing on May 3, requesting a new trial.

In federal court briefs, attorneys said jurors overlooked the eyewitness testimony that the shooter was hit by police bullets.

“Mr. Al-Amin was not responsible for the shooting; statements by both deputies that they had shot their assailant (Mr. Al-Amin had not been shot),” the appeal brief stated.

They also contended that an “FBI agent … could have planted the … weapons found after Al-Amin’s arrest.”

At the root of the case -- the defense claim that the state violated Al-Amin’s constitutional right to choose not to testify in the trial.

At issue was a slide show shown to jurors labeled, “Questions for the defendant.”

The digital presentation depicted by the prosecution posed questions to jurors like, ‘how did Al-Amin’s Mercedes get to Alabama?,’ and, ‘why would he suddenly leave Georgia for Alabama if he weren’t guilty?’”

Appeal attorneys described this as a “mock cross examination” of Al-Amin as he sat silent. The judge agreed that the slide show during closing arguments was “unconstitutional,” but insufficient to overturn the guilty verdict.

“We have enough paperwork and evidence on our side at this point to at least warrant a new trial,” said his son, Kairi Al-Amin, earlier this month.

“This case has always been about the cold-blooded gunning-down of two sheriff’s deputies in the line of duty,” said Fulton County District Attorney Paul Howard, following Al-Amin’s conviction.

Howard declined 11Alive’s interview request to discuss Al-Amin’s appeal – a longshot case for a one-time civil rights agitator, whose encounter with police could look very different through the eyes of a 2019 jury.

In a statement, Howard said in part: "Since his conviction in 2002, Al-Amin has exhausted his State appeals and is now venturing into the Federal Court System. It is my sincere hope that the conviction, handed down by a Fulton County Superior Court Jury, will continue to be upheld, and Al-Amin will remain in prison.”

For Al-Amin's son, a lot of questions still remain about that fateful night when two Fulton County sheriff's deputies were called to his Atlanta-area home.

"His schedule is five prayers a day, you could catch him at any of them ... why would he do this? Especially being the person he was in the community. He would have come (to police) in the middle of the day, why serve a bench warrant at night?" Kairi Al-Amin said. "As a Muslim ... it didn't make any sense for him to turn into Rambo (at 55) years old."

WHERE ATLANTA SPEAKS: What do you think about this case? Sound off on Twitter using #UpLateATL or on our Facebook page. Watch Doug Richards' full report tonight at 11 on Up Late.

PHOTOS: Jamil Al-Amin aka H. Rap Brown

MORE HEADLINES |