Normally when we talk about our child welfare system, we are asking why the Division of Family and Children Services and the courts didn’t do more to protect an abused child. As a community, we ask why the child wasn’t taken out of the home -- and kept out of the home.

But this is a different kind of story. This story questions whether our child welfare system sometimes goes too far. Moves too slow. Makes a mistake that harms the child more than helps.

Due to privacy laws, child welfare cases are tough to research. But the Marcus family (name changed to protect the privacy of the living children) have kept documents, email chains, text messages and even recorded several meetings. It isn’t the complete picture, but it is enough to know the system is failing this family.

It is failing these children.

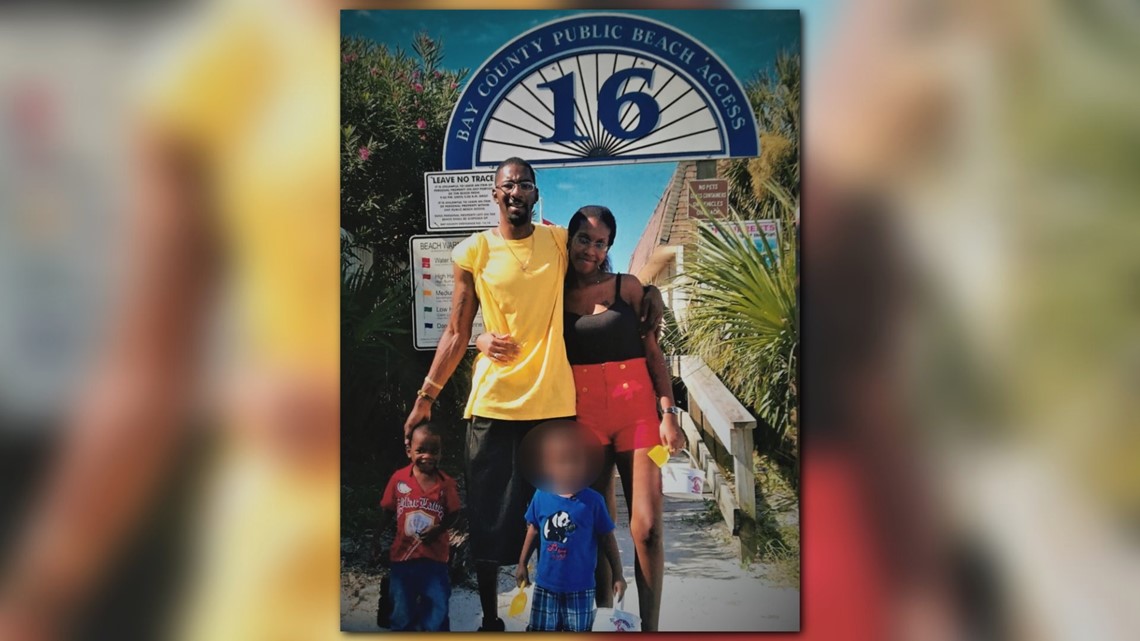

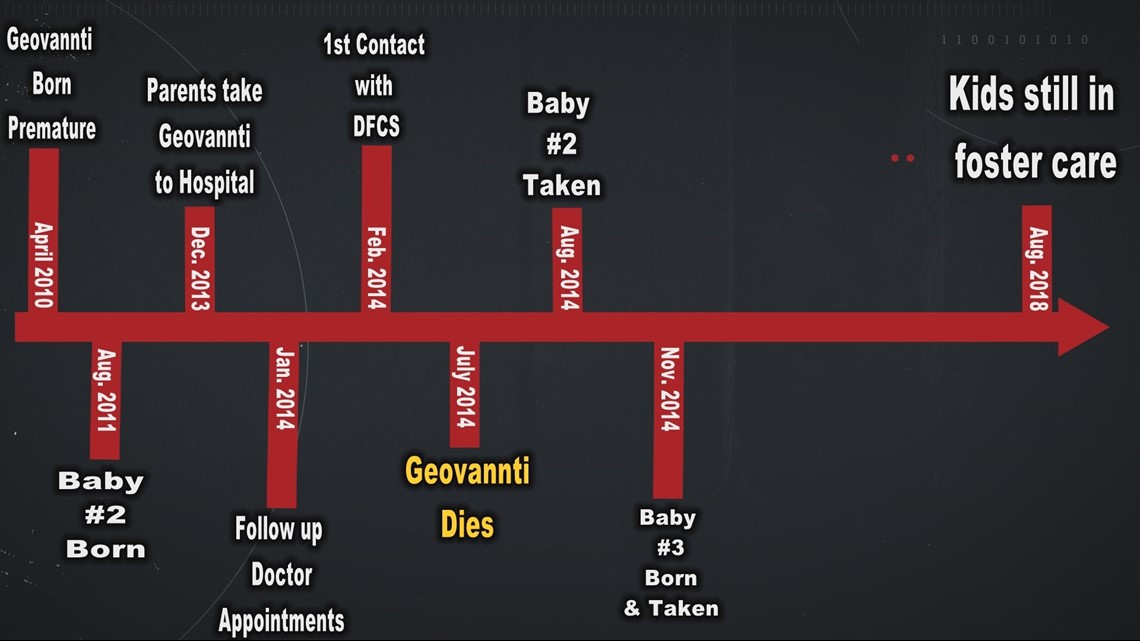

GWINNETT COUNTY, Ga. -- The Marcus’ first came in contact with DFCS in February 2014. At the time, the parents had two children, both boys, ages 3 and 4. A family member called DFCS, concerned about how the parents were disciplining their oldest son, Geovannti. They also felt the child wasn’t getting enough food.

11Alive obtained a case summary through an open records request. The report is heavily redacted, but you can see where a caseworker was assigned to visit the house within five days to see if the family needed any support services. It didn’t happen.

Two months later, the same family member called again, even though Geovannti's parents say the reporter hadn't seen him since her first call. This time a caseworker did visit, but believed the family had a logical explanation for the child’s weight. The caseworker also spent time with Geovannti’s younger brother, who according to the report, “appeared healthy and had no marks of concern on his body.” DFCS decided the children could remain in the home.

Geovannti’s mother says she told DFCS, what she told 11Alive. She would give the same information to police after Geovannti’s death.

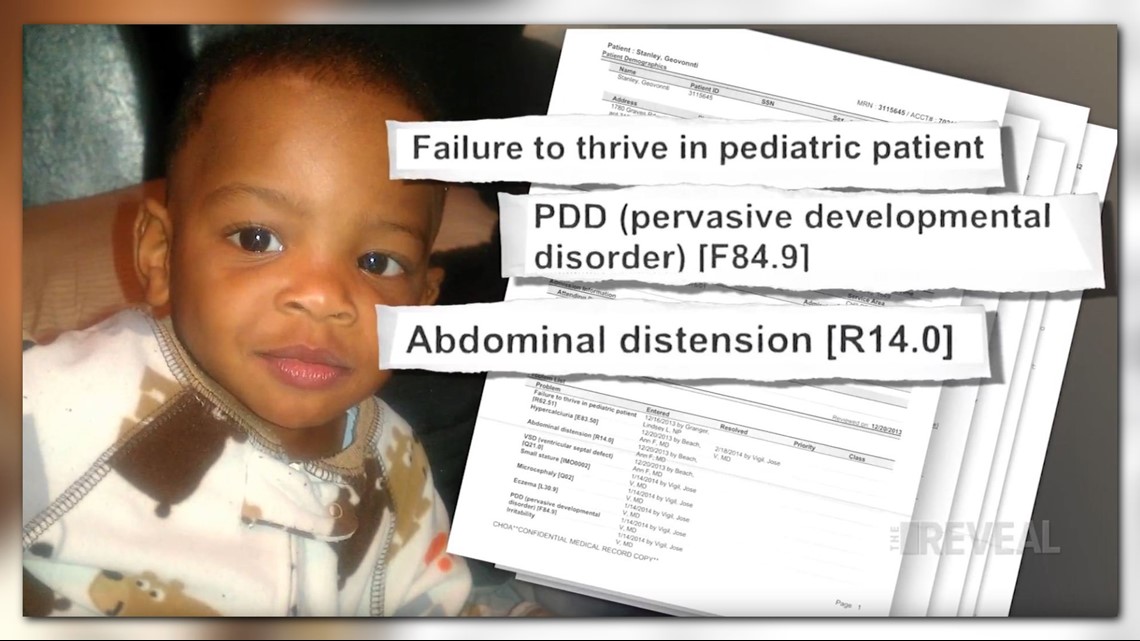

According to her, Geovannti was born at 31 ½ weeks. Other medical records say he was born at 33 weeks. Either way, he was premature weighing only 3 pounds, 6 ounces. He would spend the first month of his life in the hospital.

Geovannti would spend the next four years in and out of doctor’s offices as his parents tried to determine why he wasn’t growing as expected. He wasn’t gaining enough weight, his speech was delayed and he would have violent, physical outbursts.

His mom says the doctors all told them the same thing. “Oh, nothing’s wrong, he’s just premature. He’ll catch up.”

“He wasn’t walking or talking or doing any of the things kids his age do, but he was really, really happy," remembers his mom. "Then when he turned three, things just changed. It was like the light in his eyes just went away. You could look in his eyes and it was just dark. He wouldn’t smile. He didn’t like to be touched."

The Marcus’ say they kept going to new doctors, hoping to find one that would take their concerns seriously. Social workers and medical professionals would later question if bouncing between doctors actually delayed anyone’s ability to properly diagnose Geovannti -- or worse -- hide abuse.

► Watch the extended version of this story Sunday on The Reveal at 6pm on 11Alive

Before Christmas in 2013, the parents took Geovannti to Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta. He stayed in the hospital for four days as doctor’s ran tests. Medical records say he was eventually diagnosed with failure the thrive, pervasive developmental disorder and possibly a metabolic disorder. But doctors also began to wonder if something was happening at home, contributing or triggering his illness.

The parents were ordered to follow up with neurology, cardiology, and GI doctors. They were given information to set up appointments with the Emory Autism Center and the Marcus Institute to further investigate his developmental delays.

The parents say bad winter weather caused a few of the doctor’s offices to reschedule and Geovannti’s own behavior caused them to miss a few more. The doctors he did visit, were not able to determine a cause or treatment that would save his life in time.

On July 25, 2014, Geovannti’s mother found him dead in his bed. He was 4 years old, yet he was about the size of his 3-year-old brother. Everything about him was small, his head and his organs.

“To come home and you see the fire department and everything right there and you know you’re never going to see your son no more, that’s… that’s…” Geovannti’s father says, trailing off into the memory of that morning.

Like the doctors before, the medical examiner had no explanation. The cause of death to this day remains undetermined.

Homicide detectives did investigate. But they found no evidence to charge them with a crime. Still, a month after Geovannti died, the court ordered DFCS to remove their youngest son from the home. At the time, the mom was also pregnant. Two weeks after their daughter was born, DFCS took her as well.

“I called the homicide detective that was on the case and I said, do you have something new? Are you pressing charges?” remembers Geovannti’s mom.

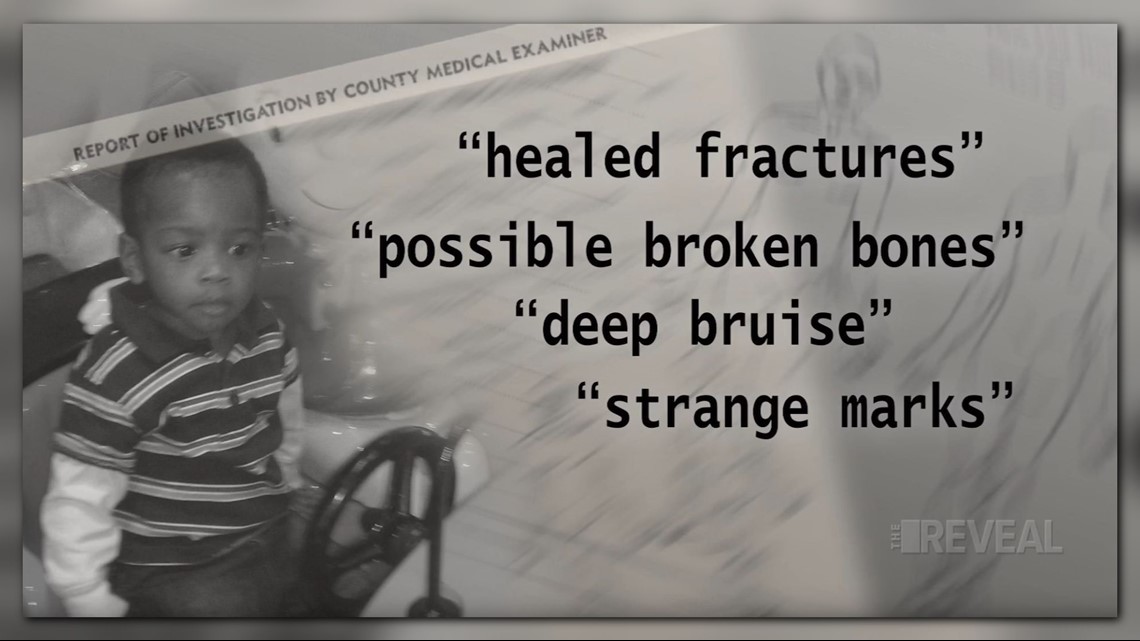

Police seemed as surprised as the parents. Both would soon learn that while no one knew how Geovannti died, the medical examiner believed at some point, he had been abused. There were signs of healed fractures or possible broken bones, a deep bruise on his butt and strange marks on the back of his head.

Police reviewed the report, but still felt there was not enough evidence to press charges for murder, neglect or even abuse. The court and DFCS felt differently.

“The agency’s role is to protect these children. And the court’s role is to protect these children,” says child welfare attorney and juvenile court judge Ashley Willcott.

While police had cleared the family, DFCS cases are civil. Different rules apply.

“Everyone has to keep in mind these are two very different systems, with different laws and different policies,” explains Willcott. “In a criminal trial as we know, it’s beyond reasonable doubt. Civil court is clear and convincing evidence. That’s a lower standard.”

But the impact is no less dramatic, because one judge now has the power to decide if these concerns are enough to rip the entire family apart, forever.

While medical experts, police, therapists and family members have testified – the information the judge must use to make his decision has changed very little in the four years since Geovannti died, triggering the remaining children to be removed. Still the family… and the children wait.

The evidence DFCS argues points to abuse, the parent’s medical expert says is further proof Geovannti was a very sick little boy.

“He would throw himself into walls, he would constantly bang his head,” said his mother.

She believes a metabolic disorder and his low body fat made him more prone to bruising and perhaps even bone fractures. After all, he was a little boy who liked to move and his parent's say was prone to violent tantrums.

Geovannti's mom called 911 and administered CPR until paramedics arrived. The parent's medical expert believes the little boys ribs could have been damaged then.

Bottom line, they were in and out of doctor’s offices. If they had physically abused their son, she says someone would have noticed.

(Video: Geovannti in his car seat)

We will likely never know how Geovannti died, or for sure, what caused the injuries on his body. Still, the Marcus’ two living children remain in foster care. While DFCS policy states siblings should be placed together, these two siblings have always been in seperate foster homes since they were taken four years ago.

There’s an empty bedroom in the Marcus’ home with a crib their daughter never slept in and toys against the wall.

“We keep the door closed,” says Geovannti’s father. “You can actually sense, like the emptiness because there’s nobody here.”

For four years, the Marcus’ have only been given a few hours each month to maintain a bond with their children, and that’s when the visits happen. Records provided by the family show stretches, sometimes as long as six months, where no visitation occurred. Last year, the court ordered the visits be supervised, in a therapeutic setting, although the family would argue there’s nothing therapeutic about them.

The mother continues to raise concerns with one of her children’s foster mothers as her son's behavior deteriorates. She begs for the right to attend his therapy sessions, or at least pick a therapist of their own. On all fronts, she is denied, even though it is the parents that still pay for the children’s medical care.

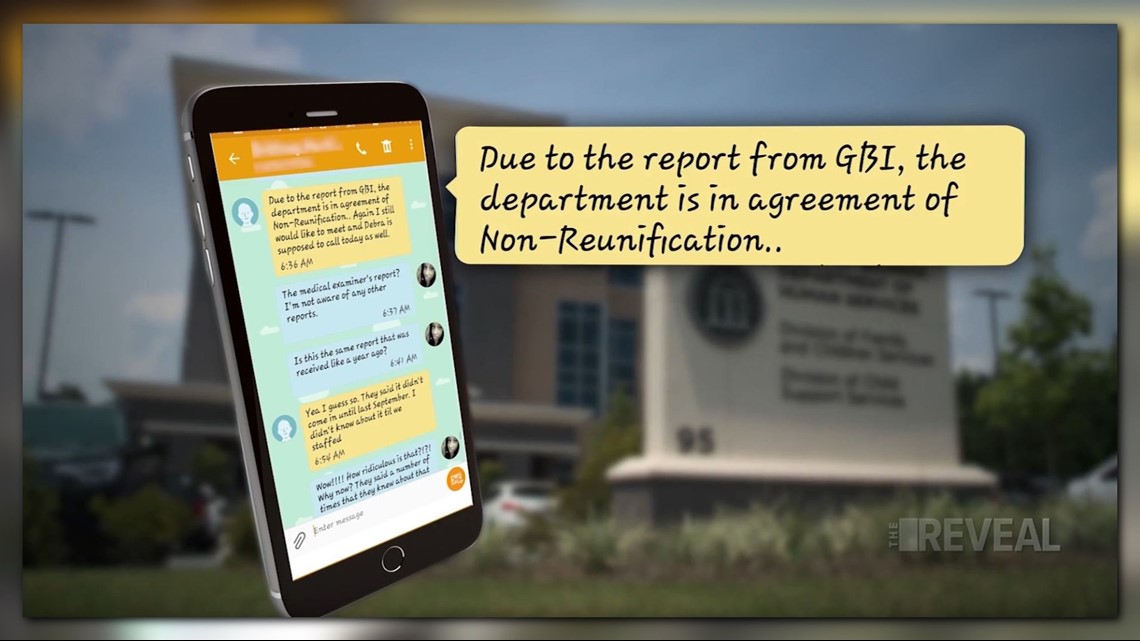

The Guardian Ad Litem, an attorney which represents the children, has always argued against reunification. DFCS gave the family a case plan, which they completed, believing their family would be restored. But in 2016, the caseworker told the parents by text message, DFCS had reviewed the medical examiner’s report again and decided to ask the judge to terminate their parental rights instead.

Along the way, there’s evidence false information about the parents has been allowed to enter the court record, promises by DFCS have gone unfulfilled leading to confusion and pain, and the parents have been denied their legal access to court records. The judge, who will ultimately decide this family’s fate, is told none of this.

The caseworkers and attorneys involved have changed over the years. It’s the parents and the children that remain the same. While there’s no date for when this case will be resolved, when it comes to our child welfare system, there’s clearly more to investigate.

We will.