ATLANTA — State Rep. Dr. Michelle Au (D-Johns Creek) exercises her voice through her vocation. The anesthesiologist decided the golden fix could come gradually through serving in the Georgia General Assembly.

"My day job, when I’m not working here is I’m a practicing physician," Au said. "One thing you realize in medicine, really early on in your career, as early as med school, you realize a lot of the problems that bring the patients to your care are really outside your ability to fix by the time they get to you.”

Au represents Johns Creek in North Fulton County, an area where Asian Americans are driving a lot of diversity. Au said Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI) make up about 4.5 percent of Georgia's population.

"This is really the epicenter of where Georgia’s changing," Au said. "North Fulton and Gwinnett County is sort of the center of Georgia becoming what’s now almost certainly a majority-minority state.”

According to Asian-Americans Advancing Justice, the Peach State's immigrant population doubled between 2000 and 2019. More than one million people born outside the U.S. are estimated to call Georgia home.

“There are many different ways to be an AAPI Georgian," Au said. "People from immigrant backgrounds are coming to America and Georgia specifically to recognize the American dream, raise their kids in an area with excellent school districts and with a lot of opportunities they look to provide their families.”

Ballot access: 'This shouldn't be a partisan issue'

But when it comes to exercising the right to vote on issues like public safety, education and economic opportunity, Au said the AAPI community gets a bad reputation.

"The stereotype is that Asian people don’t tend to turn out to vote; Asian people don’t really care about voting," Au said. "It’s not worth it to reach out to Asian voters because there are so few of them. All those things are changing, and I think in each successive election where we see AAPI voting share is growing and we’re the margin of victory oftentimes.”

Cam Ashling is chair of the Asian-American Action Fund Georgia chapter. She and her family fled Vietnam as political refugees in the 1980s. Now, she's advocating for those who speak her language. She has run political campaigns for several AAPI political candidates, honing in on issues such as healthcare and small business success that bind Asian communities together.

“This shouldn’t be a partisan issue," Ashling said. "Everybody should want safe, secure voting accessible to every eligible voter."

Ashling expressed that access to the ballot is just the start. Georgia's lawmakers should also reflect its growing Asian American population.

"Nobody can represent you better than someone who understands your culture, understands your challenges; understands language barriers we have in our community; understands the multiple facets of what we get lumped into as one community when we are multiple dozens of different communities of Asian-American voters," she said.

Ashling said AAPI voters can often feel intimidated at the polls, relying on drop boxes and absentee voting to make their voices heard.

“There are limited English voters," Ashling said. "They want to vote. It’s harder for them to drive to the polls, and they get intimidated by the voting process. They’re more comfortable if they can vote from home and they can get their kids to help them translate, then they can do it comfortably without having to go out and face what can be scary for some Asian Americans.”

Georgia's revamped election law, otherwise known as SB202, was passed in 2021. It faced scrutiny during its revision and has five central elements: new restrictions on the use of drop boxes and mobile voting, changes in absentee and provisional ballots, and an expansion on where people can serve as poll workers. Ashling said these changes were largely confusing for voters whose primary language was not English.

"The Asian American voting bloc has gotten more powerful, more influential and then we’re seeing backlash from people who want to control who gets to vote instead of the voters deciding who gets to win," Ashling said. "The more hurdles you throw at voters, you know the rate of voting drops. Without voting rights, there are no other rights. You can’t get human rights, women’s rights, religious freedom, freedom of the press, everything else. Voting rights have to be nonpartisan.”

A multilingual approach

One solution could lie in Gwinnett County.

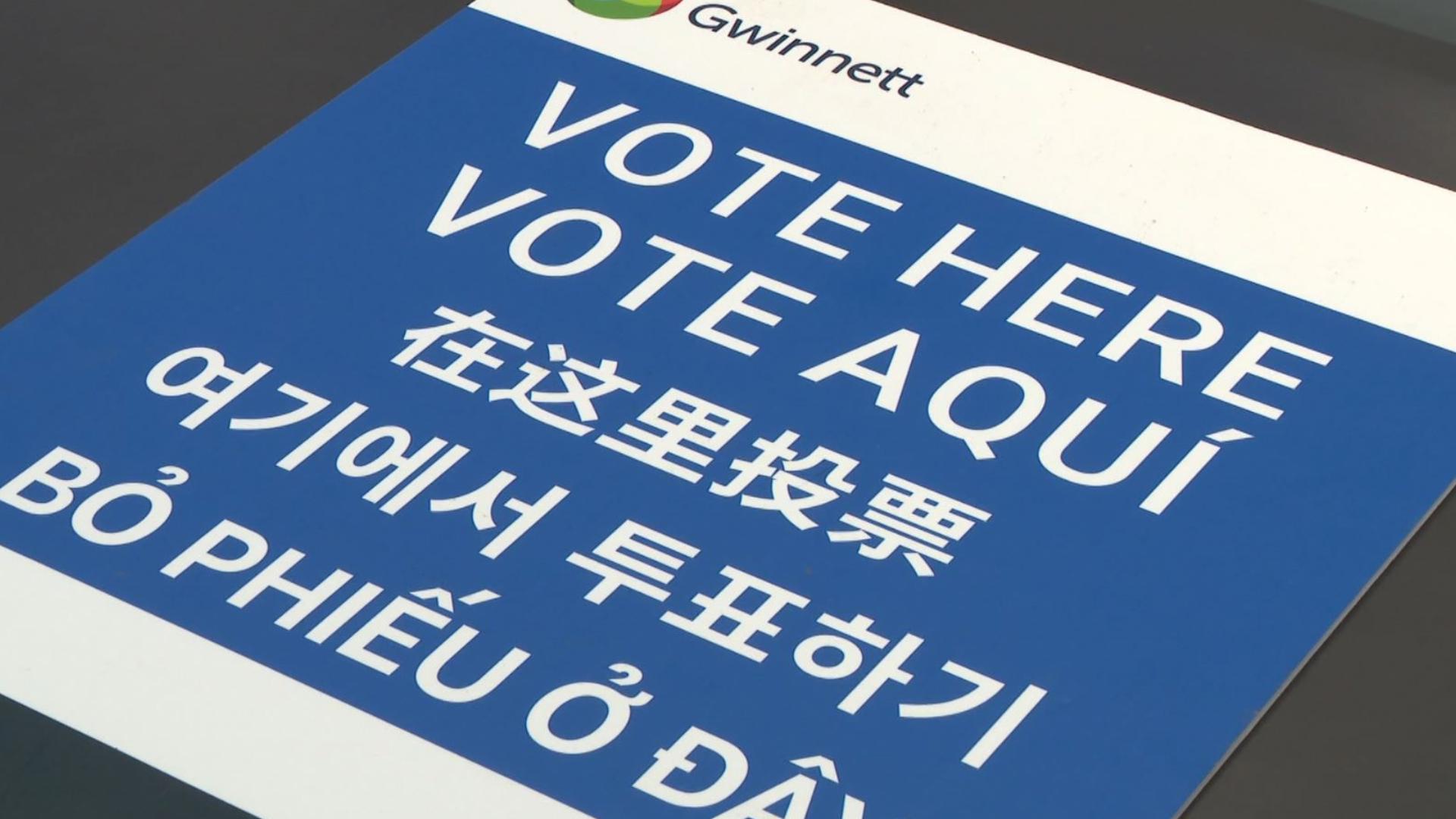

Assistant Elections Supervisor Shantell Black has worked in the Gwinnett elections office for a decade. The county rolled out the language equity initiative in 2021, with a focus on translating election-related materials to Korean, Mandarin, Cantonese and Vietnamese. To help in these efforts, Gwinnett County established language equity groups made of volunteers. These volunteers ensure the translations are accurate and serve as liaisons between the elections office and the community.

“Currently, we’re only exploring options of sample ballots, promotional materials, wayfinding signs and voting educational materials," Black said. "Gwinnett County is very diverse, and we recognize that. We want to be inclusive of all the other communities that we have as well.”

A federal requirement as part of the Voting Rights Act states that if 5% of the voting-age population in a county has limited proficiency in English, it must have an official ballot with that language. While Asian languages don't fall under this rule, yet, Black said it's still helpful for a portion of the county's population to have these items translated. Black said while the county could not trace specific voter turnout among AAPI communities, it has seen an increase in voter registration in Asian American communities.

“We realize some individuals might be intimidated by the voting process, because they may not speak the English language, so we want to make sure they have easy access to the electoral process," Black said. “They should be able to vote without any issues.”

DeKalb County became the first Georgia county to voluntarily translate its ballots into Spanish and Korean. The city of Morrow plans to have multilingual ballots in both Spanish and Vietnamese in 2025. But pushback has centered around a lack of staff and the cost it takes to make the election material. Black said the materials can add up to hundreds of thousands of dollars. With a diversifying population, Black said its worth putting in the investment now.

"We want to make sure everyone is able to express their voice and that they’re heard, that they can be part of the electoral process because they live in these communities, and the county as well," Black said. "They should be able to vote without any issues.”

Au said turning out more AAPI voters starts with engaging them, meeting them where they are and walking them through the process. She said there should be a constant reminder that one's voice matters at the ballot box no matter the language.

“We need to show them this is why it’s important for you," Au said. "This is the difference it makes. If you vote this way, these are the types of results you’ll see, these are the types of legislation you’ll be able to pass and block. So making it important to them and showing why it’s important.”