He pushed his way through the solid crowd — steadily moving past people who’d lost their homes, firefighters and officers still searching for the missing — until he reached the Butte County sheriff.

John Warner thrust the homemade flier against the tired lawman’s chest.

“I’m looking for my grandparents,” Warner said, his voice trembling, his eyes red. “I know you’re doing everything you can. But you need to do more.”

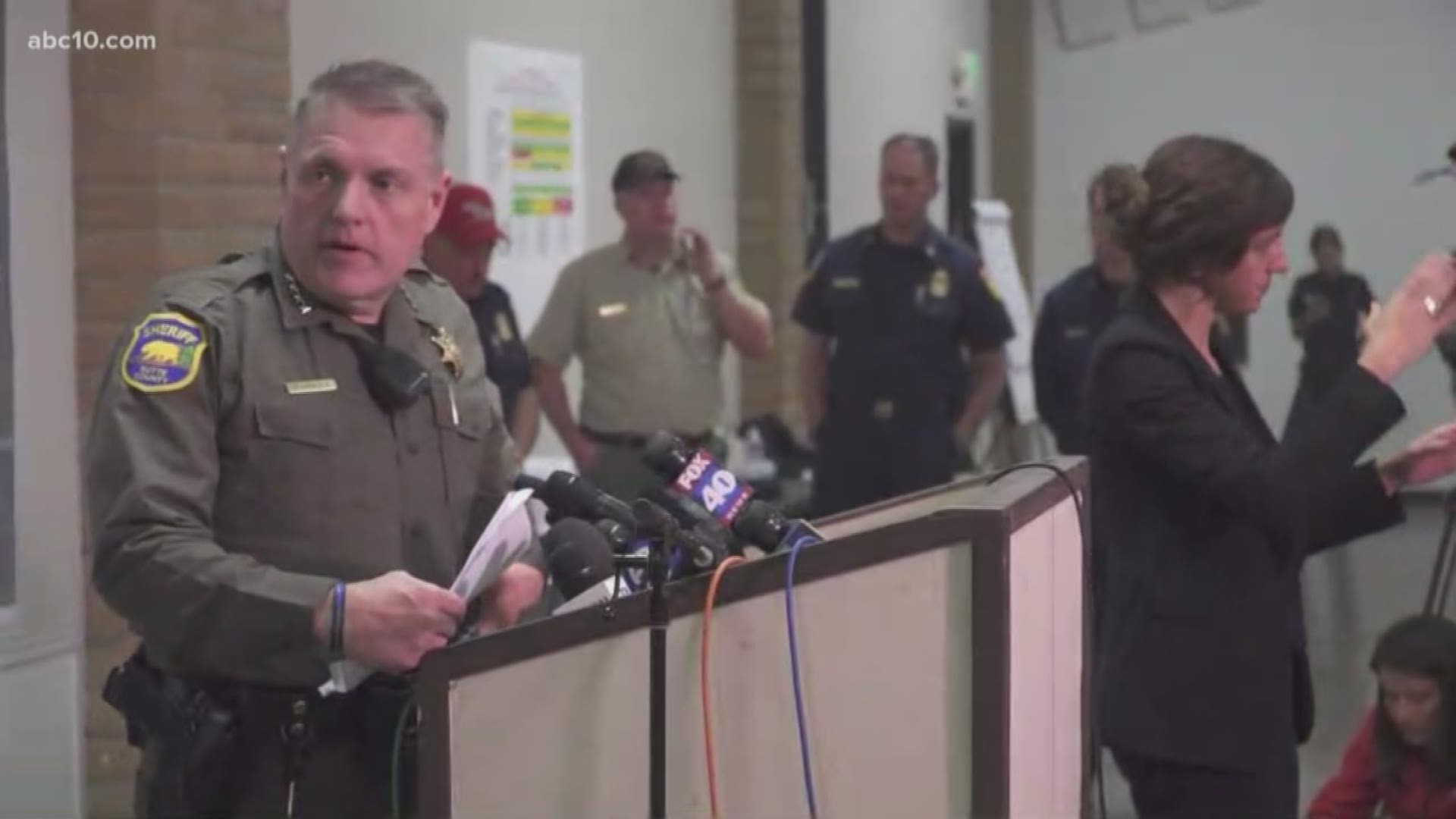

Sheriff Kory Honea had spent the past three days driving through communities ravaged by a fire that swallowed whole towns in the scenic Sierra Nevada foothills.

Minutes before, in a Chico State University auditorium filled with more than 100 people wanting answers, Honea had walked onto the stage. He knew anything he said would fall short of comfort.

People had survived chaos. Some were still living it.

“I am your sheriff and I’m also your coroner,” Honea said.

The room fell silent.

“My heart goes out to each and every one of you,” he said. “I know many are worrying about whether you have a home.”

Then, he turned to the only thing worse than losing everything you own. Three days had passed since the fire. In those three days, they’d received 120 missing-persons reports. The emergency hotlines hadn’t stopped ringing.

“That’s in addition to over 500 calls from citizens asking us to go out and check various locations for loved ones or friends who they haven’t been able to make contact with,” he said.

Mothers, fathers, husbands, wives, grandparents and friends were missing.

Officers had gone to shelters, to homes that had burned to the ground, to cars where people had become trapped by flames as they tried to escape.

They made their way through hundreds of searches and reunited many. But there were still 110 reports remaining. And there were those who didn’t survive.

“Unfortunately, to date, we have recovered 23 bodies,” he said. “We are working with teams of coroners, investigators.”

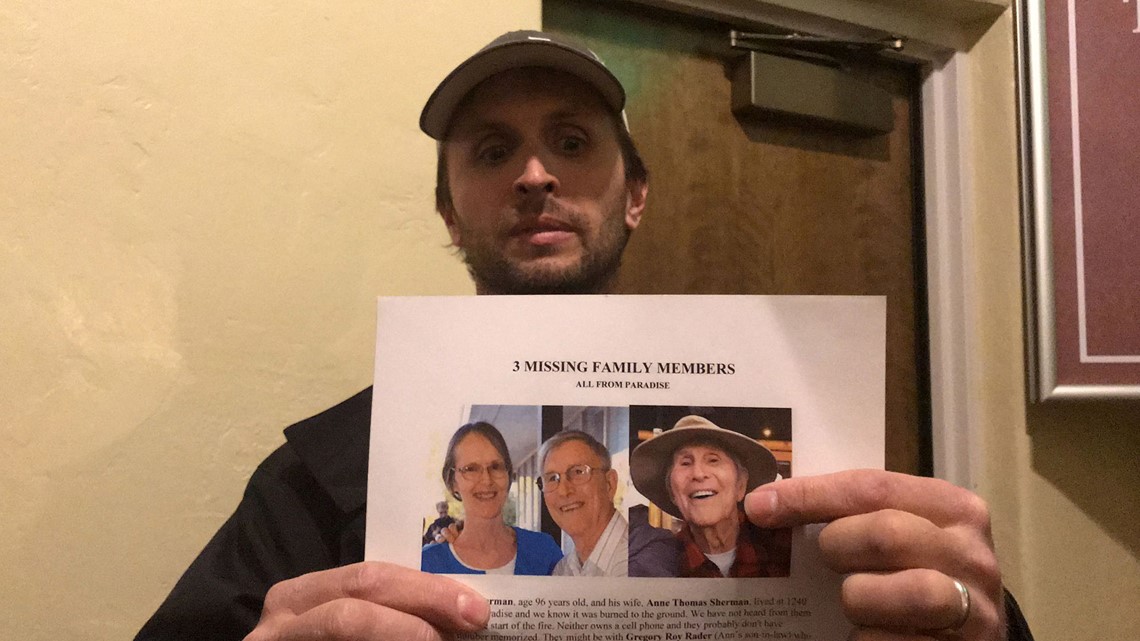

Somewhere in the crowd, John was listening, clutching a stack of fliers with two photos. One of his grandparents at a wedding. One with his grandpa, smiling in his favorite hat.

In bold at the top the flier read: “3 MISSING FAMILY MEMBERS ALL FROM PARADISE”

The last line said: “Please contact his grandson John…"

The search

John was working Thursday when he heard: Another California fire.

He stopped what he was doing. He listened. An evacuation had been ordered. People were trying to make it out of Paradise.

Paradise. No.

The scenic town of about 26,000 in the Sacramento Valley is about four hours from John’s home in Mi-Wuk Village, a scenic spot in California’s Gold Country east of Stockton

John calmed his frantic thoughts. He’d call his uncle and aunt. They also lived in Paradise and routinely checked in on his 96-year-old grandpa and his grandma, who didn’t like telling people her age. They would tell him not to worry. They would say: Everything is OK.

John had no idea what was about to happen. Soon the photos shot by trapped evacuees on their own cellphones would start flooding social media and news sites. People escaping in cars would post video of whole neighborhoods engulfed in a wall of flames.

The Camp Fire was the blaze everyone had always feared. It swallowed the canyon, moving through the North Central Sierra hills like a tsunami.

PHOTOS: The search for California wildfire victims

Soon John would discover that no one knew where his uncle Greg Rader, his aunt Michelle Sherman, his grandma Anne Thomas Sherman or his grandpa Fay Hubert Sherman were.

Over and over in the days after the fire, it was the same. Hundreds of people posting on social media, flooding law-enforcement hotlines, searching shelters.

Everyone was looking for someone they loved. Then the stories started spreading: There were people who were hurt, trapped. There were people who didn’t make it out.

John had called shelters but found the system was broken. He couldn’t get some shelters to tell him if his loved ones were there. The policy was to ensure the safety of people who might have a protection order in place.

Time and again, he was told to check the website where people listed themselves safe. John grew weary explaining that the online system wouldn’t work for people like his grandparents, who didn’t use technology.

Then, late Thursday, John spotted a news story. His uncle was listed among evacuees taking refuge at a shelter in Oroville. But amid the chaos he couldn’t get through to him to ask the one question that mattered: Are grandma and grandpa OK?

A day passed. John could no longer handle the wait. He made fliers.

He would drive to Paradise Saturday morning. He’d search every shelter, reach out to anyone who would listen.

He’d find the people he loves. He wouldn’t let himself think the worst.

His grandpa was a WWII veteran. He’d survived war and had spent 96 years living independently. John had spent his own life thinking Grandpa Fay was the strongest, kindest man he knew.

It’s going to be OK. Everyone is OK. He repeated the words like a mantra.

John hopped in his truck, driving through forests, through cities to the first shelter. It was still dark when he left home.

It’s going to be OK. Everyone is OK.

The fire came too fast

He made it to the first shelter at the fairgrounds in Yuba City.

He walked through the doors. Searched the tired faces. Asked around.

No one had seen his grandparents. He made it to the second shelter, the one in Oroville where his uncle had been listed as staying.

He saw his uncle. While he hugged him, his eyes searched the room.

His uncle told him what had happened. Aunt Michelle was safe, he said.

The fire came too fast. Greg had jumped his car, making his way up the hill, as he done so many times before to check on Fay and Anne.

But an official stopped him. A massive evacuation of an entire town was in place. He had to leave now.

John tried to make sense of what he was hearing. Three days had passed, the death toll was climbing, and no one had heard from his grandparents.

John had to call his family members and let them know. Everyone had hoped once John got to Uncle Greg, everything would be OK.

John hung up, bound for the next shelter.

There were so many. More than 25,000 people had been displaced. Makeshifts shelters in churches and the larger Red Cross shelters.

He drove to Butte County fairgrounds in Gridley, about 45 minutes from Paradise.

There, he searched faces, spoke with shelter workers.

No one had seen his grandparents.

It was dark now. John was tired. It was easier for the worst thoughts to seep in.

John made a plan. He’d heard about a community meeting for evacuees.

There, he’d talk face-to-face with officials. He’d show them his flier, the one with photos of his grandparents smiling.

'Those remains are recovered'

John walked into the auditorium at Chico State University. He listened to town officials, firefighters, police officers, health and education workers.

Two words from Sheriff Honea stuck with him: 23 bodies.

“We are going to locations where we have been told that there’s potentially human remains,” Honea said. “When we identify that there are, those remains are recovered.”

As soon as the meeting was over, John made his way to the sheriff.

“I know you’re swamped,” he said, his voice rising with frustration. He choked back tears.

Honea tried to explain. He asked for patience. But John explained that there were too many families aching for answers.

He asked why law enforcement wasn’t sharing its missing persons reports with shelters so they could help connect loved ones with desperate family members.

The sheriff took a flier. John thanked him.

He started handing out the flier to people still in the room. He searched for any media that would share his story.

“I knew I had to come find them myself,” he said in an interview with the USA TODAY Network.

“My grandpa made it through WWII,” he said. “I wouldn’t put it past him to get in his old truck and drive himself out of there.”

John shared the flier with a local news reporter. He pleaded with anyone watching. He shared his cell phone number.

The TV camera lights turned off and John planned to head to another shelter.

But his phone starting ringing. He answered. It was a shelter worker.

“What!,” he said, his eyes filling with tears. “Yes, yes. He’s the greatest man. Thank you!”

The shelter worker had seen the TV broadcast. She’d recognized the faces, the WWII veteran with the gentle smile.

John hopped in his vehicle. It was past 10 p.m. now. He drove the curvy, tree-lined roads of Chico to the church shelter.

He walked in. Searched the room.

“Grandpa, oh, grandpa!” he yelled.

And then there, standing near a cot, were his grandparents. His grandpa was wearing a blue cap with the word “veteran” on it. Grandma was sitting on the cot next to him.

Driving through flames in an old truck

Fay and Anne’s story came together in pieces.

They saw the fire. No one was there to help. Anne said Fay can hardly see anymore and their old orange truck doesn’t run well.

Anne couldn’t drive because she’s ailing and can’t maneuver a stick shift. But it was their only option as the fire raged around their home.

They hopped in the truck. Anne was Fay’s eyes.

“The fire was everywhere,” she said. “This is the most terrifying thing I’ve ever experienced. I prayed and prayed.”

“We went 15 miles an hour,” Fay said.

They made it out. It took them five hours. It was late, so they spent the night in their truck outside an IHOP.

The next day, they found Anne’s daughter, who directed them to the church shelte.

John laughed. His 96-year-old grandpa had done exactly what John had hoped.

“The old guy got in his truck and got them out of there,” he said. “I love you, Grandpa.”

“I love you, too,” Fay said.

John wrapped his arm around his grandfather. Nestled his head in his shoulder.

Everything was going to be OK.